Can graphic art assign agency and divinity to its subjects? Their aim, through colors and symbols, is to enthrall its audience to a world of imagination, built on fragments of reality wove into engrossing plots. Characters in graphic plots are in constant motion, animated with action or depicting a deep-felt emotion. In many ways, children’s cartoons, posters and comics illustrate the hyperreal in all its colorful imaginary. As Jean Baudrillard suggests on the semiotics of images, they simulate a world of meaning built on images—a palimpsest of notions that is made prominent through their assortment. Nationalist graphic art, in nations formed after a colonial rule, has a unique approach in depicting these hyperreal worlds in education, politics and entertainment. Graphic texts introduce both children and adults to a simulated reality of nationhood while promoting unity, harmony and a shared experience of the land. Posters harness the power to move people into a patriotic stupor through symbols and signs particular to contexts of freedom, nationhood and belonging. Comics, concurrently, showcase heroic deeds entrenched in complex societal and nationalist models and standards. Certain kinds of masculinity are deemed fitting for these graphic depictions of nationalist expressions while others are erased in such retellings of history and nation-making.

How detached and connected are these constructions of nationalist freedom from the colonial schema of power in graphic novels and art? If we look at Rudyard Kipling’s The Jungle Book (1894), it created a world of innocent adventure into the nature of colonial India. The work has been depicted through multiple media of representation, made accessible to all ages, classes and races of spectators. Why are we so enthralled with this world of meaning? What makes it so enticing? Mowgli is a boy-child on the cusp of developing into a man who presents a link to the unknown flora and fauna of subcontinental India by dint of being raised by wolves. The aspect of gazing upon the exotic is its primary mode of operation. Edward Said’s framework of the Oriental being created through the Occidental gaze fits like a glove in Kipling’s narrative style. Mowgli is a half-human discovered in the forests by the colonial surveyor trying to make sense of this unknown natural habitat. This interaction between the British Raj (British empire) in colonial India and Mowgli, is shown as a desire on both ends to make known the machinations of empire and the exotic nature that encompasses this empire.

Mowgli (Disney, 1967)

In current depictions, Mowgli is the focus of the story—animated in 1967, 1994 and most recently, 2018 as motion pictures. The plot is not about the Jungle anymore. This is a significant shift from the unknowable land to the boyish link who knows the land. Unlike Tarzan, another boy who became a man in the African jungles, Mowgli is fixed in his boyish nature. His significance is inherent in not growing up and remaining a forever link for the Occidental gaze to survey as deep and as wide as the desire to exoticize can go. Another important difference between the two fictional characters, is that Tarzan is white where Mowgli is brown. Tarzan is not just the link for the empire, he is a representation of the empire who is in tune with the colonial landscape fully. The masculine mastery of African jungles is fully established through Tarzan becoming a man completely embroiled in the African landscape. Mowgli, on the other hand, is always in a state of development representing the consistent exotic call of the Indian subcontinent that is bereft of a fully developed masculinity.

Tarzan fighting a cheetah (Disney 1999)

In both depictions, there is a need for man to preside over nature that is always open to discovery, conquest and adventure. Masculinity is also performed in the bodies of agile men and boys. This presents the colonial desire to construct certain kinds of masculine bodies in varied colonized wilderness for ease of accessibility and allocation of the gaze of power.

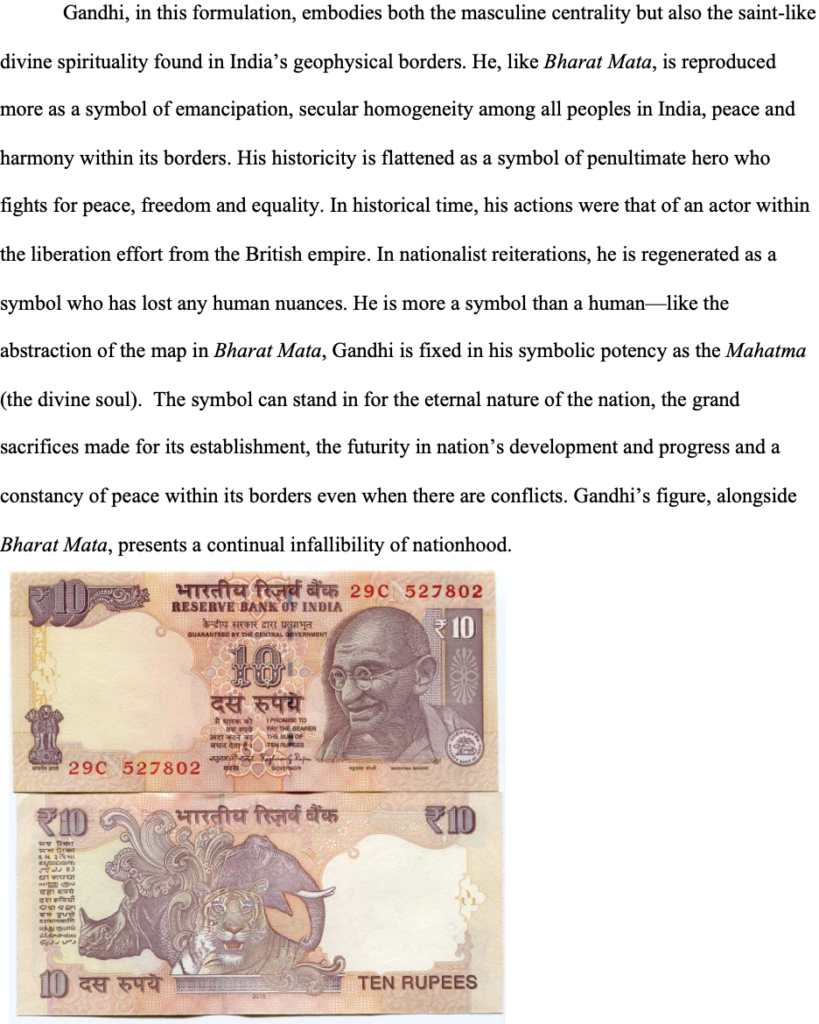

Continuing from this premise of masculine control over colonial forest lands—vast, wild and unknowable—there is the anti-colonial development of nationalism. What remains as a continuation are men who can stand in as representation and construct an alternate modern state divorced from the colonial structures of power. Unlike fictional means, the nationalist world of meaning is developed through a historical narrative of a perpetual nation. Here, images of powerful masculine iconoclasts create the hyperreal symbolic world of nationalism. The fact that they existed in time, had proximate subjectivity to the masses and carried a sense of independence in their bodies and dispositions render nationalism in perpetuity. Their images signify, the homogenous reproduction of a singular nationhood since the space of nationalist inspiration remain fixed in the body of the Father of Nation. The nation, geographically, historically and ideologically is almost always rendered stable in the body of this perpetual Father.

For the sake of this discussion, I will only discuss the image of Gandhi and the image of Mujib or Bangabandhu in this reproduction of nationalist meaning through perpetual national Fathers. This is not to deny their importance in the cause of nation-making but rather to examine their symbolic significance that is made undeniable and absolute, posthumously, as the only path to freedom and self-determination. From the fictional premise of Mowgli and Tarzan to the historical symbolization of national fathers, there is a shift in agency as masculinity. Here the Occidental gaze is replaced with the nationalist gaze that seeks a self-reflection. There is a desire to be seen as the Self in the body of the Father. Seemingly, there is no ‘other’ in the nationalist formulation since nationalism unlike colonialism seeks to eradicate differences in sovereignty and a notion of absolute freedom. Colonialism has always been critiqued as a source of making differences among its subjects—categorizing, rendering legible and legalizing different bodies.

Nationalism represents a counter to that. There is an emphasis on all as one and so the figure of the Father is crucial in promoting a sameness in the nation. When nations are seen as postcolonial, there is almost an implicit reference to sameness being justified in its formulation. As nations are formed in an emancipatory narrative, the historical narrative plays an important role in embodying facts with an absolute masculine leader whose presence quiets all dissonances. The postcolonial predicament is almost eradicated through this symbol-making, where heroes stand in for all humans of the nation.

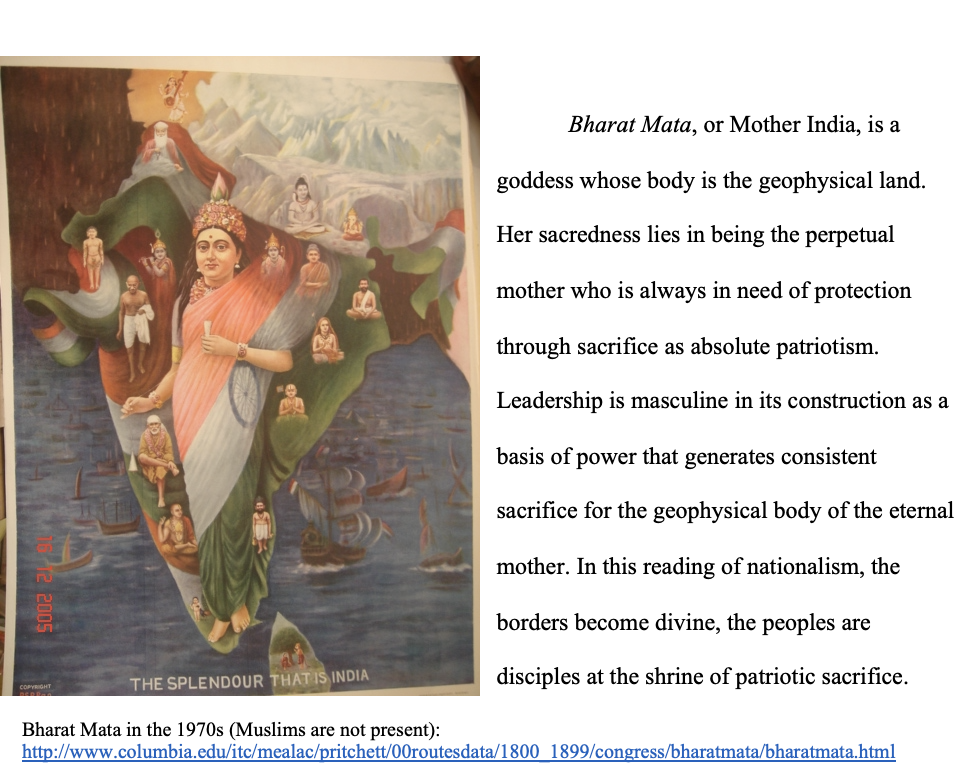

Sumathi Ramaswamy explores this notion of nation in perpetuity under the image of Gandhi in India. Her work is mostly on images that explore the generation of symbolic meaning of the nation. The materials she works with are graphic in their nationalist ability to propagate patriotism—maps, images of goddesses, martyrs, patriots and Gandhi. There is a sacredness that is attached to these pictorial meaning-making. The images come after the fact of history. There is a triangulation among the Father, the heroes of the nation and Bharat Mata. Notice how the only mention of womanhood, Bharat Mata, is in the body of the map both abstracted and extracted in its contours. Ramaswamy sees this triangulation as justification for homogeneity among the populace but also the establishment of a heteronormative value to nationhood in post-independence India. There is an implicit assumption that land represents womanhood that is led, construed, protected and exploited by the masculine figure of the leader or the colonial surveyor.

Gandhi on an Indian 10 rupees note

There is a heteronormative structure that is established in the nationalist framework. The reference to perpetuity makes the heteronormative sacrosanct. Symbols invoke certain kinds of performance that bleeds into the national psyche. Hence, in current times, there is an abhorrence to anything that appears different from the normative. The radical work of sacrifice and nation-making is already past. Post-colonial is rendered a real condition where everything is in harmony in its sameness. Anything else is treasonous. All other voices are in opposition to the nation’s historicity and its sacred space. While posters and symbolic images are rooted in political conversations, the turn to comics might seem relieving.

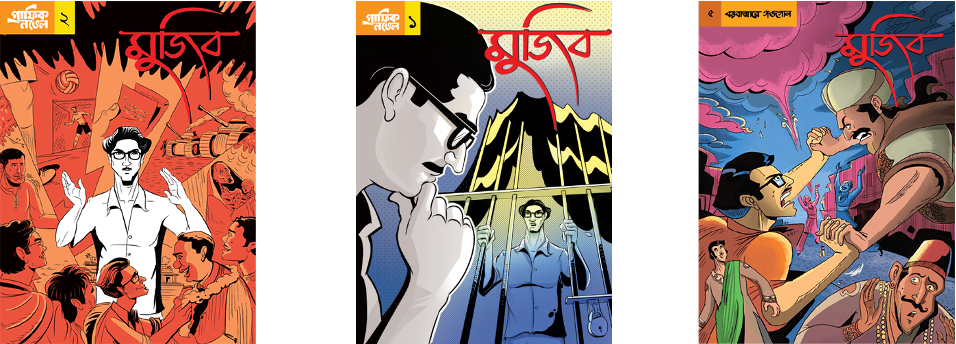

As a moment of commemorating Bangabandhu (friend of Bengal), Sheikh Mujibur Rahman, the government of Bangladesh published a website with a series of animated graphic novel. The site introduces the novel as: “These engaging comics present the life of Bangabandhu Sheikh Mujibur Rahman and his anecdotes in an effort to pass on the history and knowledge of the Father of the Nation, Bangabandhu Sheikh Mujibur Rahman, to the younger generation.” The image of Bangabandhu is reified to present a more youthful version who is always ready for action. Although, the website claims a historical connection, the representation is meant to engage a younger audience in a fictive Bangabandhu.

The images above are a preview of each segment in the series. There is a detective-like aura around the figure of Bangabandhu. The first image amplifies his youthful physique, surrounded by various sports references. The second shows a more thoughtful Mujib, deep in anxiety about freedom for fellow countrymen stuck behind bars. The last is Mujib in action against evils presented in men wearing different kinds of jewellery and clothing. Bangabandhu’s historical presence, therefore, is subsumed within his fictive, moral, and youthful representation. Posthumously, he inspires a moral futurity for Bangladesh. He is a father but also a friend in this symbolic rendition. Here, the nation is reflected as individual noble acts that leads to a perpetual sovereignty. While Bangabandhu was an eminent political leader in the subcontinent, he never really fought in the war for Liberation. By reassigning him as a youthful, belligerent and heroic figure, his historicity is flattened to an individualistic effort for freedom. Here, history becomes quintessentially that of a great man—nationhood is fixed as a culmination of all the good deeds of an individual man.

Conclusion

Engaging with graphic art is like entering a world made only of symbols. If you know references, each symbol can hold its own story and can even speak for its silences. In this piece, I attempted to discuss my interests in reiteration of colonial novels into graphic animation for children to nationalist symbols and how they are represented in graphic art. The relation of power has been a consistent apparatus of covert dialogue between colonialism and nationalism. This can be read in its nuances when we read innocuous media that are meant to entertain.

Works cited

Baudrillard, Jean, 1929-2007. Simulacra and Simulation. Ann Arbor: University of Michigan

Press, 1994.

Said, Edward W. Orientalism. New York: Knopf Doubleday Publishing Group, 2014.

Websites visited:

https://mujib100.gov.bd/pages/mujib/graphic-novel.html

Disney images from Google

2 responses to “Graphic Representations of Colonial and National Masculinities in the South Asian context”

What a beautifully presented piece. Thank you for making full use of our new HASTAC Commons features. I’ve tweeted it too.

Thanks for the comment! Means a lot. This is work is part of my research questions/thoughts so all comments and feedback is always appreciated