Today I spent most of the day rummaging around in the Rare Book & Manuscript Library in Butler Library at Columbia University. I am new to archival research, and much enjoying this research methodology!

The collection I was studying is the McDougal collection. The collection is an extensive collection of papers from the professional documents of Gay J. McDougall. McDougall is one of the leading international human rights legal champions, and led the Lawyers Committee for Civil Rights Under Law Southern Africa Project from 1980 – 1994. The collection ranges in date from 1932 – 2006, with the bulk from 1960 – 1994 during the peak of the anti-apartheid struggles in Namibia and South Africa.

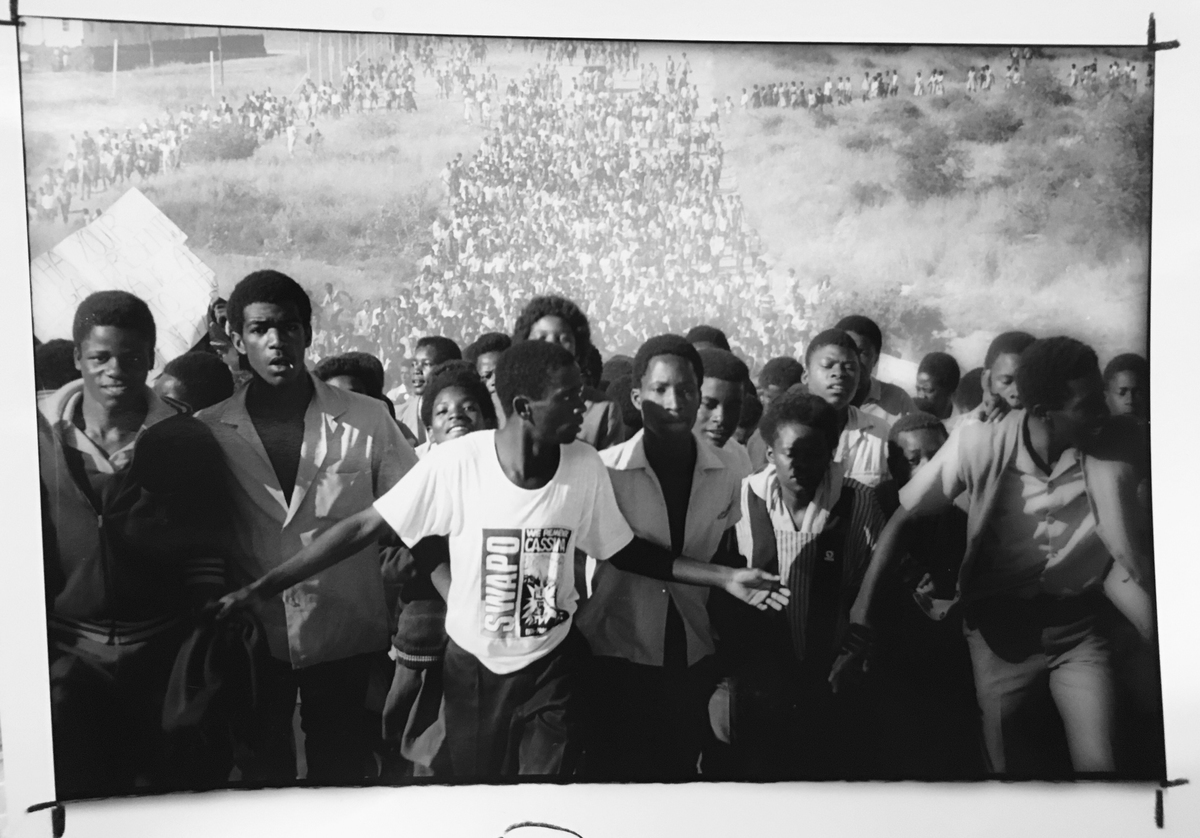

Perhaps the most striking “discovery” was the collections of photographer John Liebenberg. Looking through these photos was so absorbing that the rest of the reading room seemed to melt away. Some are graphic and disturbing, depicting the barbaric violence of the South African Defense Force and the graphic torture they deployed to maintain power in Namibia. Others, such as this one, which depicts marchers paying their respects for the 10-year anniversary of the Cassinga Massacre, show the strength and conviction of the Namibian people. The Cassinga Massacre took place in 1978 during Namibia’s struggle for independence. Namibia’s liberation movement, the South West African People’s Organization (SWAPO) had established struggle camps in various countries to support the War of Independence. At one of those camps, in Cassinga, Angola, approximately 600 Namibians were killed by the South African Defense Forces. The photo below asserts strength and resilience, declaring: “we carry on despite these horrific setbacks.” If you look closely, you can see hundreds of people rallying behind the man leading the group. So many people lost their friends and family members in the fight to end apartheid, but as a family friend of mine told me, they knew they were fighting for a cause much greater than themselves – a free Namibia.

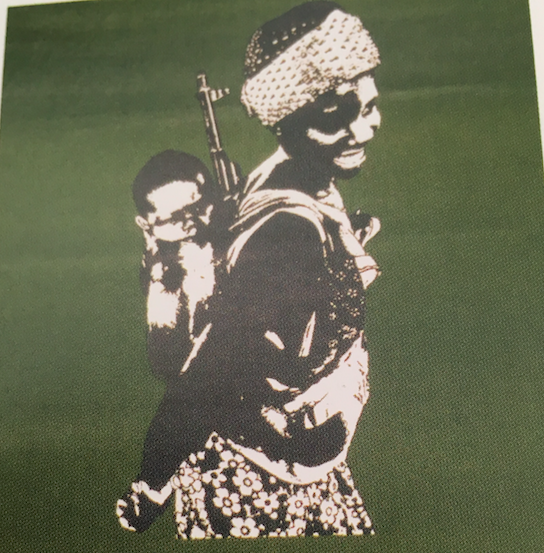

These photos speak to me because my research also analyzes anti-apartheid posters such as the one shown below. I find these posters compelling because they portray women anti-apartheid struggle heroes as both warriors and as mothers. An example is shown here:

The McDougal collection is expansive. The sheer magnitude of Gay McDougall’s documented work and the volume and scope of her projects and leadership is impressive. (And I only looked at 11 of the dozens of boxes that are available to the public!) Many of the documents are official United Nations files. Others are human rights reports such as those published by Amnesty International and other local human rights organizations. There are also dockets from legal defense organizations and files documenting visa applications for asylum and refugee-seekers seeking to break from the dangers in Namibia for anyone resisting apartheid.

In Women, Gender, and Sexuality Studies, we are taught to read against the grain of the archives. This concept of queering the archives, of reading through and beyond what is there to seek what may NOT be documented is an important part of trying to capture the until-now unseen and unheard heroes of history. For example: I spent a long time reading through a newsletter entitled, Namibia News Briefing. (See image of the publication below.) This publication was published by a human rights watchdog organization, and each edition features a section called Repression. It details some of the violence and mistreatment dealt to SWAPO and Namibians during the anti-apartheid struggle. I was able to find a number of women detailed in the periodical, but not many. Not nearly as many as the men. And when they are mentioned, it is often in connection to their husbands. It leaves me wondering: what other stories are out there, left untold? One of my mentors calls this a “commemorative desert” – a place in history where memories and formal documentation or commemoration are absent. Of the women I did read about, their bravery is clear and apparent. I can’t help but continue to think: how would or could Namibia change if young people knew these stories of their elders? How did Namibia’s history create ruptures and fissures which indelibly altered the trajectory of its history? Given the violent past of Namibian history, what would Namibia be like today if it had not been colonized by Germany, subjected to one of the world’s first genocides, then later scarred by the vicious and violence white supremacy of the apartheid regime? And perhaps most importantly: how can the country heal and move forward? Is today’s scourge of GBV and femicide in Namibia linked to this past? Does paying homage to the past and working to reconcile and better understand the past assist in moving the country forward in a balanced, healed manner?